|

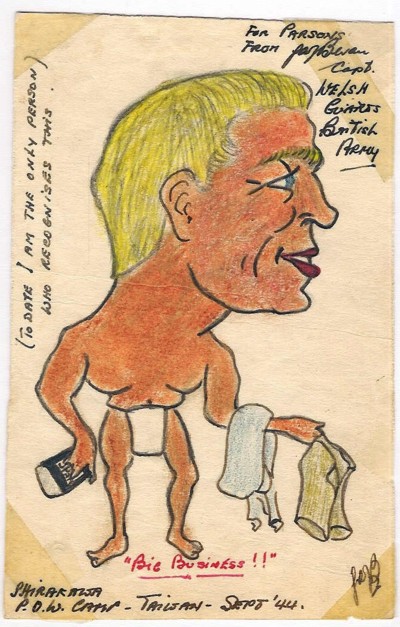

March 21, 2005 Tom, I am forwarding the attached article written by Ron Parsons from New York. Ron was on our recent trip to the Philippines. His father (John Edwards Parsons) was a survivor of the Bataan Death March and died in 1965. His dad was depressed the rest of his life after that experience. Ron was drafted into the Marines during the Vietnam War and was wounded three times. He has two Purple Hearts for war injuries. He was awed by the trip to the Philippines. Ron is submitting his work to a local New York paper. Ted Cadwallader... March 17, 2005 "It isn't much but it is all I have to say thank you. I hope you like it. Ronnie In the year 2005 American newspapers will be replete with articles concerning the end of World War II: epic battles of the Bulge, the ruins of Berlin. There will be stories of heroes and the headlines will remind us all that the atrocities of Auschwitz, Buchenwald, and Dachau should never be revisited. Then there was finality with Hiroshima & Nagasaki. There is another story, one where thousands of Americans were held prisoner. It’s a story few are alive to tell and it may soon be lost forever. It was the darkest time in American history. While cameras were rolling on Nazi Death Camps filled with the dead of other nations, the American dead and skeletal prisoners of the Japanese were being hidden from view. Four per cent of American prisoners died in German hands. Seventy per cent of the American prisoners captured on Bataan died in Japanese captivity. It was death from starvation, beatings, sadistic cruelty and outright mass murder. The members of the “2005 Back to the Philippines Tour” attended a dinner on February 3rd, 2005. It was the 60th anniversary of liberation of the Philippines at the former Internment camp at Santo Tomas University in Manila. The reunion began with the Star Spangled Banner sung by Las Vegas performer Beth Mullaney, daughter of a former internee. Bataan Death March veterans stood side by side with American civilian prisoners and the liberators of Manila. American Ambassador Ricciardone and Philippine Senator Gordon offered an emotional eulogy to those present and gone. Later a full orchestra and choir performed. Bob Holland, one of the only U.S. Marines with General Macarthur’s invasion force, called “the flying column”, told me of his book during dinner. Hampton Sides, author of “Ghost Soldiers” sat across from us. After the performance some of the internees of Santo Tomas guided us to the rooms where they lived as prisoners. (Robert Holland wrote "Rescue at Santo Tomas.") I felt like an intruder to the almost 50 people on our tour, but in a sad way I was one of them. The organizer, Sascha Jean Jansen, welcomed me because my father was on the Death March. The group accepted me as one of its own. In 12 days we did what could definitely be called a whirlwind tour of past battlefields and present monuments to the fallen Fil-American Force from World War II. It puzzled me because many with us looked so young. When I asked several it readily became apparent that they were American children interned as prisoners by the Japanese. Earl was in his mid 60’s, but certainly looked much younger. His leg is in a brace, and he walked with a heavy limp. He admitted this was his first time back to the Philippines since “the War.” “I was about 11 months old,” he said. “My mother was holding me and a large piece of shrapnel from a Japanese shell dislodged me from her arms, leaving my leg like this and wounding my mother.” Later in the day, alone, Connie Ford shared with me how she and her family nursed Earl back to health. She said, “They may have been the first civilians wounded in the Philippines.” This was the first time they had met in 60 years. She said Earl was mentioned in the book, “We Band of Angels.” He is now a law professor at the University of Virginia. On day 6 the tour bus stopped at the Clark Field cemetery. There was an American tending one of the over 8,000 graves. He looked unshaven and disheveled as he occasionally chose a tool from the bed of his old Toyota pick up. His work was meticulous but it was the dry season now in the islands. The once opulent grass was in God’s hands. Anyone could tell this wasn’t his first day maintaining the grave site. John sat across from me in the bus. He was built like an English bulldog and asked me to accompany him as we walked up to the volunteer grounds keeper. John held out his hand and asked, “Hi. My father was killed in Australia 2 months before the war and I haven’t been able to find his grave. We have narrowed it down to here.” “I’ve been looking after this site for over a decade and know nearly every grave. What’s his name?” “The same as mine, John Hinck.” The grounds keeper lifted his worn black Vietnam veteran’s hat and took a couple of seconds to think. “John, I believe he’s right over there in row A, about in the center.” By this time 5 or 6 people had gathered around us. John gave a very sincere “Thank you.” holding his wife’s hand he walked to that area. He asked me to come with my camera. On the walk he shared with me the circumstances of his father’s death. At 77 John is a newly wed. “My father was in the U.S. Army in Philippine intelligence. He died in November of 1941 on assignment in Australia and his body was sent back here by ship as the war started. The funeral procession was harassed by Japanese zero fighters. His body was moved and I, till now, didn’t know where he was buried. The rest of the family was interned by the Japanese in Santo Tomas.” Soon, John was kneeling at his father’s grave – touching the white stone. I was fortunate to get several pictures for him. He has them on his wall at home. Each person in our group had an amazing story of survival, circumstance, and hardship. Many of them are authors and there was a documentary film crew with us. On tour day 10 we were allowed access to the American Embassy in Manila. We went through several profile checks even before entrance. Security was very high because a package had just been blown in place by Embassy security at the gate. Many of the pictures adorning the interior walls were of American heroes, guerrillas and the spies of World War II that served in the Philippines. On stopping at one picture in the annex our escort related events there-in. “Yes”, Margaret Squires said defiantly. “That’s a Japanese propaganda photo of me washing my mother’s hair. Mother told me not to look up at the Japanese photographer.” Farther down the line a man pointed to another picture. “That one is of me.” Our Ph.D. escort was more than duly impressed. She was awe struck. I had begun to take such events in stride. Day 7 was a free day on the tour and in exiting the Manila Hotel I met a lady from our group. She gracefully accepted my offer for dinner when I told her where I planned to dine. Little did I know her story. Sunsets are rapid and often brilliant near the equator, as it was this evening on Manila Bay. In what seemed like moments it was near dark and sparkles from fireworks overhead glistened on the “old Army/ Navy Club’s” Olympic sized pool’s surface, crystal clear without a leaf or flaw. Our restaurant table happened to be next to the pool. In the distance a Chinese New Year’s celebration erupted with the brash clanging of gongs. The metallic sound echoed on the warm breeze from the city as the procession edged ever closer, bringing the change. In her eyes I saw the dissonance of a lady now embraced by peace but always recognizing the sacrifice of those who were forced to endure war. War, America’s rite of passage. The waiter uncorked our wine. “Douglas Mac Arthur was an investor in the gold mine my father managed on Mindanao, The Mother Lode.” She said. “My father felt our safety at risk early in 1941 when the military sent all of their dependents state side. Mac Arthur was a good friend. I use to play with his son Arthur, not many feet from here. I spent much of my youth in this pool. We felt the Mac Arthur family faced the same risks we did. How wrong we were.” Mary McKay Maynard carried a defiant brightness that occasionally flashed in her eyes as remembrance. “The General was very convincing you know.” (Mary McKay Mayard also wrote the book "My Faraway Family.") For a moment I could envision General Douglas Mac Arthur pacing the waxed mahogany floors of his penthouse suite in the Manila Hotel flamboyantly gesturing with his signature corncob pipe. History always portrayed him as the brilliant military tactician. Mac Arthur, who often spoke of himself in the 3rd person, was first in the 1903 class at West Point. He could recall dates, places, and commanders from battlefields eons ago with flowing verbiage that mesmerized foreign and American businessmen over after dinner cognac. “Yes” Mary said, “He told us there was no threat from the increasingly war like Japanese. He said we would whip them in a matter of weeks if they grew hostile. After all, Dwight David Eisenhower was once his aid de camp in the Philippines. Mac Arthur knew everyone and everyone knew he was privileged to information on the highest level.” She lifted her glass of wine and toasted the air, drank and said, “On December 8th Manila time over 5,000 American citizens were trapped here in the Philippines when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. We had all believed we were safe. We believed Douglas MacArthur.” After dinner I walked alone back along the old Dewey Boulevard (now Roxas Blvd. - pronounced Rowhaus) away from our tour’s domicile at the Manila Hotel. I desperately tried to collect my thoughts. For months I had psychologically prepared myself for the geography of the Philippines and the battlefields of World War II. For instance, on the island of Corregidor I noticed that every one of the huge battery guns were made by the Watervliet Arsenal only a few miles from my home in New York. I wondered how many soldiers from New York died touching a piece of home. I am no stranger to the Orient for I had served in the Marines in Vietnam. I was neither a stranger to combat wounds nor to the jungle. I felt I knew what to expect. There was something I hadn’t expected to find on this trip. It was the people, the American civilians I’d met on the 60th Anniversary tour that had totally “blind-sided” me. Many of them were children when captives (internees) of the Japanese. In the first 6 months of War the Japanese captured nearly 350,000 allied citizens & POW’s. Prisoners were a new experience for the Japanese military. I sat on a bench and looked out onto Manila Bay to Cavite, America’s old Navy Yard. I dreamed, placing myself right here in 1941, watching the men walk about the boulevard dressed in their white linen suits, wearing panama hats and smoking cigars. At their sides were some of the most beautiful Eurasian women in the Orient. It was the idyllic colonial life here in Manila, before the war. Manila was called the “Pearl of the Orient Sea.” By this time there were throngs of young celebrants along the wide boulevard next to the bay. They infected everyone with jubilation of the coming year; brightly colored paper dragons wove their serpentine way through the crowd. The dragon’s head jerking up and down… sideways. The multitude of slippers underneath danced on one foot then another with the music’s beat, strings of fireworks exploded.  John Edward Parsons On October 24, 1941 my father, John Edward Parsons of the 803rd Army Engineers, looked over the railing of the troop carrier at Cavite to a new land, to a land of what must have seemed like a great adventure. The depression years had been tough but they were all behind him now. Little did he realize that in 6 months he’d be on the infamous Bataan Death March and prisoner of the Japanese Empire for a torturous and starving 3 ½ years. He would die in 1965, the year of my high school graduation, after terrible suffering and incapacitating disability for 6 years. During that time the Veteran’s Administration gave my mother and me $143 a month. I remembered the last thing I said to Mary, “We share a common bond because the Japanese stole my youth too.” It was the first time I saw emotion in her eyes. Mary’s parents left her an orphan at age 15. I made a mental note to buy her book. My mind returned to the day our tour had followed the path of the Death March. For every kilometer of the Death March there is a concrete obelisk in memorial. We traveled through the nearly unchanged barrios where Filipinos risked their own lives in 1942 to throw my father and other American soldiers bits of rice rolled in banana leaves. Many natives were shot or bayoneted by Japanese guards for their attempts to feed the starving Americans. My father mentioned it many times. I will be forever grateful to the people of the Philippines, and they will always be special to me. I know, because my father was bayoneted and survived. There were children playing in the yards now amongst beautiful coconut palms. It was one of life’s paradoxes as to how a place so peaceful and beautiful could hold such a terrible secret. I remembered our group leaving the bus in silence to walk the last kilometer of the Death March. Each person carried with them the silent dignity of their own memories. Many were 80 plus, but I could never match their spirit. The sun was unmerciful even that early in the morning. It took a lot for me to walk the last stretch of road to the monument listing the 1,650 American dead at the Camp O’Donnell POW compound. I remembered what my father told me about the “Death March” with tears in his eyes – how many friends he’d lost.  This caricature was done in prison camp of Dad (he was a horse trader-they called him "Abe" as they call a bald man hairy), I think Shirakawa. Ron  2 Russians that freed him at Mukden (Hoten) Manchuria. John is in the center Each person with us knew that all the Japanese war criminals were released from prison by 1952 after serving only 7 years, even on life sentences. Every former prisoner knew that the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, signed by America, forbid American prisoners from seeking monetary reimbursement for their illegal slave labor during the war. The Peace Treaty’s primary author, John Foster Dulles, argued it would be too much of a financial burden on Japan and Japanese corporations, who were in the process of rebuilding their nation after the war. To him, it was unthinkable to compensate the American POWs for their slave labor. Many of those same corporations are huge Japanese conglomerates today. Each person knew that America did not get an unconditional surrender from Japan. Each person now walking in silence on the March of Death knew that America had forsaken its sons and daughters then as it did now. On Bataan the soldiers sang the poem that marked their identity. It became their anthem. No mama, no papa, no Uncle Sam; No aunts, no uncles, no cousins, no nieces; No pills, no planes, no artillery pieces; and nobody gives a damn.”  or would like to be added to my POW/Internee e-mail distribution list, please let me, Tom Moore, know. Thanks! |